24 KiB

What we'll learn

You'll learn three things at the same time so don't get discouraged if it feels a bit much at the start. Everybody's issues will be in these three different domains and at the beginning it can be difficult to differentiate between them. Keep this in mind, everybody has to go through this stage and the click comes at different times for different people but everybody clicks at some point! The three new things you'll learn:

- the concepts of programming, most notably Object Orientated Programming (OOP)

- the syntax of one particular language, in our case Python3

- the tools needed to start programming in our language of choice

Within each of these topics there are subtopics but there are not bottomless! Below is a small overview of how I would subdivide them.

Concepts

The subtopics behind the concept of programming can be sliced (in no particular order) as follows:

- objects or OOP (Object Orientated Programming)

- abstraction

- encapsulation

- inheritance

- polymorphism

- variables (which are not boxes in python3)

- conditional logic

- functions

- loops

The concept behind these topics are the same in most languages, it's just how you write them that is different. This how is part of the syntax of the language.

Syntax

In computer science, the syntax of a computer language is the set of rules that defines the combinations of symbols that are considered to be correctly structured statements or expressions in that language. This applies both to programming languages, where the document represents source code, and to markup languages, where the document represents data. The syntax of a language defines its surface form.[1] Text-based computer languages are based on sequences of characters,

The quote above is taken shamelessly from wikipedia.

Tools

Writing code

Scripts are text files, plain and simple. So in order to write a Python3 script all we need is a text editor. Nano, vim, notepad++ all do a good job of editing plain text files but some make it easier than others. You've noticed that vim colors the code of a shell script no? One of the many features of an IDE is syntax highlighting. It colors things such as keywords which makes our life so much nicer when writing code. We'll come back to these features in a bit.

Running code

In order to run Python3 code you need the Python3 interpreter. This is because when you execute your script, the interpreter will read and execute each line of the text file line by line.

Most people who want to write and run Python3 code, or any language for that matter, will install an Integrated Development Environment to do so. There are no rules as to what has to be included for a program to qualify as an IDE but in my opinion they should include:

- syntax highlighting

- autocomplete

- goto commands such as goto definition, goto declaration, goto references

- automatic pair opening and closing

- builtin help navigation

There is a plethora of IDE's available and you can't really make a wrong choice here, but to make the overall learning curve a bit less steep we'll start out with a user friendly IDE, pycharm.

The python3 shell

TODO animated overview of the shell and the world of OOP

Installing pycharm

TODO

Your first project

In almost any language you'll find a helloworld program. It serves to illustrate a very basic working script or program to showcase the syntax. In python a helloworld is done as such.

print("Hello World!")

Just for reference below are a few helloworld programs in different languages.

First c# then c and last but not least javascript.

Console.WriteLine("Hello World!");

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

printf("Hello World!");

return 0;

}

alert( 'Hello, world!' );

How to execute

- within pycharm

- from the command line

Simple printing

The most basic printing can be done by calling the print function.

In python a call is symbolized by the ().

In practice this becomes as follows.

print("hello world")

print("my name is Wouter")

print("I'm", 35, "years old")

🏃 Try it

Try printing different lines and with combinations of different object types such as int, float and str.

What happens if you add (+) values to one another?

We can also print the objects referenced by variables. A simple example:

name = "Wouter"

age = "35"

print("Hello, my name is", name, "and I'm", age, "years old.")

While it works perfectly well it's not super readable. We can improve the readability by using either string replacement or string formatting. My personal preference is string formatting.

🏃 Try it

Have a look at both ways illustrated below and try them out.

String replacement

name = "Wouter"

age = "35"

print(f"Hello, my name is {name} and I'm {age} years old.")

String formatting

name = "Wouter"

age = "35"

print("Hello, my name is {} and I'm {} years old.".format(name, age))

Some links to read up

Taking input

The first builtin function we saw is print which can be used to signal messages to the user.

But how can we get some information from the user?

This is done with the input function.

If we open up a python shell we can observe it's behaviour.

>>> input()

hello world

'hello world'

>>>

It seems to echo back what we type on the empty line.

If we take this idea and add it to a script the behaviour changes slightly.

The prompt appears but when we hit enter the text is not printed.

This is one of the slight nuances between running scripts and using the shell.

The shell is more verbose and will explicitly tell you what a function returns, unless it doesn't return anything.

Some functions are blocking

When we call print the function is executed immediately and the python interpreter continues with the next line.

The input function is slightly different.

It is called a blocking function.

When a blocking function is called the program is waiting for some action.

Once the condition is met, the program continues.

It's important to be aware of this but don't overthink it.

We'll get back to this behaviour later.

Functions can return something

So, functions can return something but how can we use the returned objects?

This is where variables come in handy.

The input function will always return an object of type str.

If we want to use this object later in our code we need to add a post-it to it so we can reference it later.

Remember that the object is created by the function call, and we add the reference after the object's creation.

print("What is your name? ")

answer = input()

print("Well hello", answer, "!")

When looking at the code block above did you notice the empty space I added after my question? Can you tell me why I did that?

🏃 Try it

Try playing around with the input function and incorporate the different ways to print with it.

Ask multiple questions and combine the answers to print on one line.

Functions can take arguments

Some, if not most, functions will take one or more arguments when calling them.

This might sound complicated but you've already done this!

The print function takes a-message-to-print as an argument, or even multiple ones as you probably noticed when playing around.

The input function can take arguments but as we've seen does not require an argument.

When looking at the documentation we can discover what the function does, how to call the function and what it returns.

⛑ CTRL-q opens the documentation in pycharm

Help on built-in function input in module builtins:

input(prompt=None, /)

Read a string from standard input. The trailing newline is stripped.

The prompt string, if given, is printed to standard output without a

trailing newline before reading input.

If the user hits EOF (*nix: Ctrl-D, Windows: Ctrl-Z+Return), raise EOFError.

On *nix systems, readline is used if available.

We can add one argument inside the input call which serves as a prompt.

Now which type should the object we pass to input be?

The most logical type would be a str that represents the question to ask the user no?

Let's try it out.

answer = input("What is your name?")

print("Well hello {}!".format(answer))

🏃 Try it

Modify the questions you asked before so they have a proper prompt via the input function.

Ask multiple questions and combine the answers to print on one line with different print formatting.

Taking input and evaluation

We can do a lot more with the input from users than just print it back out. It can be used to make logical choices based on the return value. This is a lot easier than you think. Imagine you ask me my age. When I respond with 35 you'll think to yourself "that's old!". If I would be younger then 30 you would think I'm young. We can implement this logic in python with easy to read syntax. First we'll take a python shell to experiment a bit.

>>> 35 > 30

True

>>> 25 > 30

False

>>> 30 > 30

False

>>> 30 >= 30

True

>>>

The True and False you see are also objects but of the type bool.

If you want to read up a bit more on boolean logic I can advise you this page and also this.

This boolean logic open the door towards conditional logic.

Conditional logic

Let's convert the quote below to logical statements.

If you are younger than 27 you are still young so if you're older than 27 you're considered old, but if you are 27 on the dot your life might be at risk!

age = 35

if age < 27:

print("you are still very young, enjoy it!")

elif age > 27:

print("watch out for those hips oldie...")

else:

print("you are at a dangerous crossroad in life!")

⛑ Do not fight the automatic indentation in your IDE! Pycharm is intelligent enough to know when to indent so if it does not indent by itself, you probably made a syntax error.

Class string methods

Let's take the logic above and implement it in a real program. I would like the program to ask the user for his/her name and age. After both questions are asked I would like the program to show a personalized message to the user. The code below is functional but requires quite a bit of explaining!

name = input("What is you name?")

age = input("What is you age?")

if age.isdigit():

age = int(age)

else:

print("{} is not a valid age".format(age))

exit(1)

if age < 27:

print("My god {}, you are still very young, enjoy it!".format(name))

elif age > 27:

print("Wow {}! Watch out for those hips oldie...".format(name))

else:

print("{}, you are at a dangerous crossroad in life!".format(name.capitalize()))

An object of the type str has multiple methods that can be applied on itself.

It might not have been obvious but the string formatting via "hello {}".format("world") we did above is exactly this.

We call the .format method on a str object.

Strings have a handful of methods we can call.

Pycharm lists these methods when you type . after a string.

In the shell we can visualize this as well.

For those of you not familiar with shells have a look at tab completion.

>>> name = "wouter"

>>> name.

name.capitalize( name.format( name.isidentifier( name.ljust( name.rfind( name.startswith(

name.casefold( name.format_map( name.islower( name.lower( name.rindex( name.strip(

name.center( name.index( name.isnumeric( name.lstrip( name.rjust( name.swapcase(

name.count( name.isalnum( name.isprintable( name.maketrans( name.rpartition( name.title(

name.encode( name.isalpha( name.isspace( name.partition( name.rsplit( name.translate(

name.endswith( name.isascii( name.istitle( name.removeprefix( name.rstrip( name.upper(

name.expandtabs( name.isdecimal( name.isupper( name.removesuffix( name.split( name.zfill(

name.find( name.isdigit( name.join( name.replace( name.splitlines(

>>> name.capitalize()

'Wouter'

>>> name.isd

name.isdecimal( name.isdigit(

>>> name.isdigit()

False

>>> age = "35"

>>> age.isdigit()

True

>>>

⛑ Remember CTRL-q opens the documentation in Pycharm and don't forget to actually use it!

Some links to read up on

- realpython conditional logic

Coding challenge - Celsius to Fahrenheit converter

Your first challenge! I would like you to write a program that converts Celsius to Fahrenheit. The result of this program could be as follows.

➜ ~ git:(master) ✗ python3 ex_celcius_to_fahrenheit.py

What's the temperature?30

30°C equals 86.0°F

Go turn off the heating!

➜ ~ git:(master) ✗ python3 ex_celcius_to_fahrenheit.py

What's the temperature?4

4°C equals 39.2°F

Brrrr, that's cold!

➜ ~ git:(master) ✗ python3 ex_celcius_to_fahrenheit.py

What's the temperature?blabla

I can't understand you...

➜ ~ git:(master) ✗

If you want to make the program a bit more complex, try adding the reverse as in Fahrenheit to Celsius. Your first question to the user could then be in which direction do you want to convert?.

Spoiler warning

result = input("What's the temperature?")

if result.isdigit():

celsius = int(result)

else:

print("I can't understand you...")

exit(1)

farenheit = celsius * (9/5) + 32

print("{}°C equals {}°F".format(celsius, farenheit))

if celsius < 15:

print("Brrrr, that's cold!")

else:

print("Go turn off the heating!")

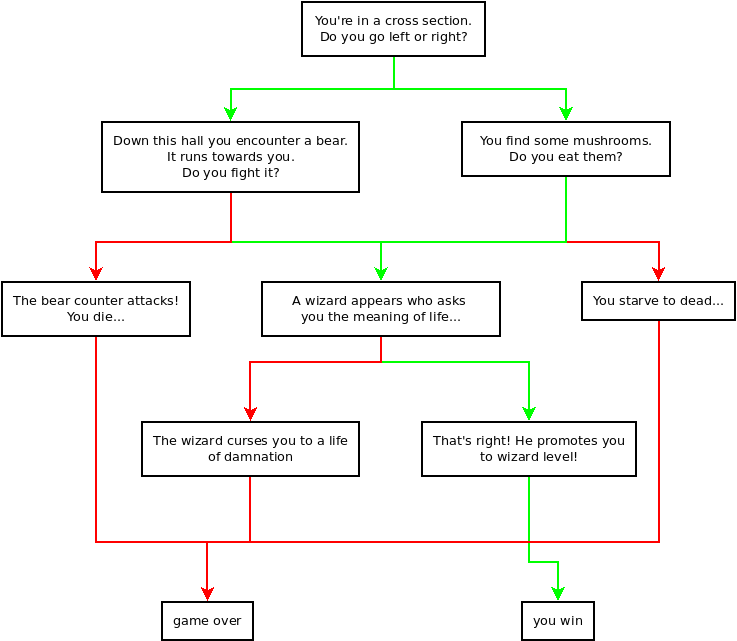

A text based adventure game

We can use conditional logic to create quite elaborate decision processes.

Let's build a mini text based adventure game.

Granted it's not a tripple A game but it will train your if and else skills plus it will highlight some issues we'll overcome in the next section.

Consider the diagram above we can imagine a program that functions nicely with the code below. It is not very readable nor scalable.

answer = input("You're at a cross section. Do you go left or right?")

if answer.startswith("l"):

answer = input("Down this hall you encounter a bear. Do you fight it?")

if answer.startswith("y"):

print("The bear counter attack! He kills you")

print("game over!")

exit(0)

elif answer.startswith("n"):

print("It's a friendly bear! He transforms into a wizard!")

answer = input("The wizard asks you if you know the meaning of life?")

if answer == "42":

print("He knods approuvingly and upgrades you to wizard status!")

print("You win!")

exit(0)

else:

print("He shakes his head in disbelief. You fool!")

print("game over!")

else:

print("that's not a valid choice...")

print("game over!")

exit(0)

elif answer.startswith("r"):

answer = input("Down this hall you find some mushrooms. Do you eat them?")

if answer.startswith("n"):

print("You starve to dead...")

print("game over!")

exit(0)

elif answer.startswith("y"):

print("A wizard apprears out of thin air!")

answer = input("The wizard asks you if you know the meaning of life?")

if answer == "42":

print("He knods approuvingly and upgrades you to wizard status!")

print("You win!")

exit(0)

else:

print("He shakes his head in disbelief. You fool!")

print("game over!")

else:

print("that's not a valid choice...")

print("game over!")

exit(0)

pass

else:

print("game over!")

exit(0)

I urge you to read up on some best practices for if statements.

We will not improve on this particular example but I do advise you to create a similar style game during one of the workshops once we have learned some new tricks.

Creating your own functions

One of the issues we have in the text based game example is duplicate code. At two spots we execute almost identical code and this is something that should be avoided at all costs! Why write the same thing over and over? You're better off writing it once and use it lots. This is where functions come into play.

Python ships with a lot of built-in functions but we can create our own very easily.

The keyword to define a function in python is def.

All the code that is indented will be executed when we call the function.

Here is a basic abstraction of correct syntax.

def first_function():

print("I'm a function")

print("Hear me roar!")

If you type only the code above in a new script, and run it, you won't see much. This is because you only created the function. To use it you need to call it. This is done as follows.

def first_function():

print("I'm a function")

print("Hear me roar!")

first_function()

Learning how to create functions is a big step in your programming journey. It can seem confusing at first because the code execution appears to jump around. This is however not the case. Your script is still read and executed line by line so you can not call a function before you defined it! For now you should not overthink the structure of you scripts. As long as they work you should be happy. We'll dive into the proper anatomy of a program real soon.

Functions that do something

The first function I showed you above performs a series of actions each time it is called. We can use it to bake cakes for example. Below we create one function to bake the cake, and call it three times to bake three cakes.

def bake_chocolate_cake():

print("mix the base ingredients")

print("add the chocolate flavour")

print("put in the oven")

print("enjoy!")

bake_chocolate_cake()

bake_chocolate_cake()

bake_chocolate_cake()

Now, you might like a vanilla cake from time to time. Easy, we'll just write a second function for that purpose.

def bake_chocolate_cake():

print("mix the base ingredients")

print("add the chocolate flavour")

print("put in the oven")

print("enjoy!")

def bake_vanilla_cake():

print("mix the base ingredients")

print("add the vanilla flavour")

print("put in the oven")

print("enjoy!")

bake_chocolate_cake()

bake_chocolate_cake()

bake_vanilla_cake()

bake_chocolate_cake()

bake_vanilla_cake()

Voila, we can now make as many chocolate and vanilla cakes as we want!

But what about bananas?

Following our logic we can create a third function to bake a banana cake but you're probably seeing a pattern here.

Each bake_FLAVOR_cake function is almost identical, just for the flavoring.

We can create one generic bake_cake function and just add the custom flavor each time we actually bake a cake.

This is done with arguments.

def bake_cake(flavor):

print("mix the base ingredients")

print("add the {} flavor".format(flavor))

print("put in the oven")

print("enjoy!")

bake_cake("chocolate")

bake_cake("vanilla")

bake_cake("banana")

Variable scope

Variable scope might sounds complicated but with some examples you'll understand it in no time.

Remember variables are like unique post-its?

Well, variable scope is like having multiple colors for your post-its.

A yellow post-it with name on it is not the same as a red one with name on it so they can both reference different objects.

Scope is where the colors change, and this is done automatically for you in python.

It's an inherent feature of the language but the concept of scope is not unique to python, you'll find it in most modern languages.

Now, some examples.

total = 9000

def function_scope(argument_one, argument_two):

print("inside the function", argument_one, argument_two)

total = argument_one + argument_two

print("inside the function", total)

function_scope(300, 400)

print("outside the function", total)

Here total outside of the function references a different object from the total inside of the function.

Python is very nice and will try to fix some common mistakes or oversights by itself.

For example.

name = "Wouter"

def function_scope():

print("inside the function", name)

function_scope()

print("outside the function", name)

But we can not modify the referenced object from inside the function.

This will give an UnboundLocalError: local variable 'name' referenced before assignment error

name = "Wouter"

def function_scope():

print("inside the function", name)

name = "Alice"

function_scope()

print("outside the function", name)

There is however a handy keyword we can use to explicitly reference variables from the outermost scope.

This is done as follows with the global keyword.

name = "Wouter"

def function_scope():

global name

print("inside the function", name)

name = "Alice"

function_scope()

print("outside the function", name)

Functions that return something

TODO basic math functions

Some links to read up on

- some best practices for functions

- more details on variable scope

Coding challenge - Pretty Print

Can you write me a function that decorates a name or message with a pretty character. Kind of like the two examples below.

##########

# Wouter #

##########

#################

# Python rules! #

#################

Spoiler warning

def pretty_print(msg, decorator="#"):

line_len = len(msg) + (len(decorator) * 2) + 2

print(decorator * line_len)

print("{} {} {}".format(decorator, msg, decorator))

print(decorator * line_len)

pretty_print("Wouter")

pretty_print("Python rules!")

pretty_print("Alice", "-")

Using the standard library

TODO import random exercise (digital dice) TODO import datetime exercise (will it be Sunday) TODO simple ROT13 cryptography with multiple libs

Coding challenge - Memento Mori calculator

Writing your first library

TODO import pretty print and digital dice

What are libraries?

How do we write libraries?

What is __name__ == "__main__"?

Anatomy of a program

TODO imports, functions, execution

While loop

TODO guess the number exercise

Lists

Creating lists

Picking elements

Slicing lists

For loop

TODO say hello to my friends exercise

Coding challenge - Cheerleader chant

TODO nested for loop exercise

Handling files

Reading from a file

Writing to a file

csv, JSON and yaml

pickle

Coding challenge - Login generator

TODO write a login generator as a library with a cli as program BONUS argparse, save to file, read from file

Dictionaries as data containers

TODO adapt the login generator to output a dict

Creating our own classes

Class examples

TODO simple animal or vehicle exercise TODO task manager

Class inheritance

TODO shapes and surfaces TODO superhero game

Improve the login generator

TODO convert the login generator to a class

Infinite programs

- insist on the nature of scripts we did up until now

Logic breakdown of a simple game

TODO hangman exercise

Trivial pursuit multiple choice game

TODO db

Introduction to the requests library

Threading

TODO add a countdown timer to the multiple choice game

- how apt does it's progress bar